“WHERE THERE IS HOPE, THERE IS LIFE: AN ALTERNATIVE TO PHYSICIAN-ASSISTED SUICIDE, CONSIDERING CHINESE AND WESTERN PERSPECTIVES ON LIVING THROUGH TERMINAL ILLNESS IN CHINA”

Author: Philip Hung-wong Chiu, Hons. B.Sc. (Psychology) with 1st Class Honor (McGill); M.D.(Queen’s, Canada), F.R.C.S.(C), F.A.C.O.G. ; M.B.P.A. (UC Irvine); M.Div. & Th.M. (Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, now Gateway); M.A. (Pastoral Care and Counseling) & Ph.D. (Psychology & Practical Theology) from Claremont School of Theology. See Facebook and Youtube.com under Philip H Chiu.

Abstract:

What is it that prompts the tormented terminally ill to choose life, instead of killing themselves? The thesis here presented is that hope can provide them a positive attitude to remain engaged in life. Many of the peasants and “urban poor” in China are in a dilemma when afflicted with a terminal illness: on the one hand, they can ill afford even pain relief; and on the other, their requests for Physician Assisted Suicide cannot be honored because it is still illegal in China. Interdisciplinary literature review suggests that hope appears to be uniquely suited to deal with the existential concerns of these people. Field work in Southern China also lends support to the thesis.

Chapter One outlines the challenges of providing health care in China. Using interviews conducted by the author, Chapter Two describes some of the ways people live through terminal illness in China, and how they manage to find meaning and hope in their cultural beliefs, strengths and values. Chapter Three explores, from the perspective of the Western philosophical tradition, the question that some of these interviewees are asking: What is my meaning of life? This brings into discussion the views of both the “True world” and “Continental” philosophers.

An interdisciplinary discussion of hope (Chapter Four) suggests that four dimensions of hope, the first virtue in life followed by will, may be uniquely equipped in addressing the needs of the terminally ill. Chapter Five examines the question “Is Fostering Hope Justified in the Terminally Ill?” ethically, existentially, and scientifically. Chapter Six outlines different ways as to how hopefulness can be fostered by caregivers, with due respect given to the unique cultural setting of the afflicted. In conclusion, it appears that when the terminally ill have hope, they remain engaged in life, making Physician Assisted Suicide less of an issue. It should be noted that the author’s social location as a Southern Baptist minister, an endorsed chaplain, and a retired physician trained in Western medicine may have lent predispositions and biases to the interpretation of literature and research interviews.

This book outlines a strategic intervention in pastoral care that focuses on care for the terminally ill and their families (essentially in Chapter 6). For this reason, this book may be of interest not only to spiritual caregivers, but also to students of the social sciences and healthcare personnel such as nurses and doctors. I do hope that my contribution can also serve as a catalyst to continuing dialogues between health care policy makers, spiritual caregivers and the public. Together, we can offer the best end-of-life care to all concerned.

Introduction

During my 15 months of service as a spiritual caregiver[1] and counselor in a major hospital in China, I was saddened by the intractable pain and suffering[2] of a number of terminally ill[3] patients who requested Physician Assisted Suicide (PAS) because they could not afford the expensive palliative care. They were in a dilemma. Some of them had spent all their life savings on medical care. Thus, many were already heavily into debts, which had created considerable financial burden on their families. To stay the course would have meant suffering the indignity of wasting away under the ravages of their disease, and incurring further debts and burdens on their families. They wanted to die, but were unsure about the best way to end their lives with dignity. Knowing that I am a physician as well as a spiritual caregiver, they asked me about PAS, thinking that somehow I could advise them or even help them with this “good death” (an le si in Chinese, or “mercy killing” as PAS is known in China). I was in a dilemma too. First, PAS is still illegal in China. Second, my Christian faith and my commitment to the Hippocratic Oath[4] would not allow me to do such a thing, even though I empathized with their suffering. Suicide by any means raises serious issues: ethical, socio-cultural, politico-medico-legal as well as spiritual and relational. I propose another option: fostering hope as an interventional strategy, based on the thesis: where there is hope,[5] there is life.[6]

The Core Problem in its Relevant Contexts

China is a country in transition. Her entry into the 21st century has been marked by astonishing economic growth and prosperity, but not without cost. There is now a wider disparity between the rich and the poor. China’s transition from state-owned businesses to free enterprise has left many of her citizens without adequate healthcare, which used to be provided by the state. When confronted with a terminal illness, the poor often cannot afford the expensive care and pain relief at the hospital. Neither do they have any kind of hospice program to alleviate their suffering and provide them support at home. No wonder more and more of these patients are asking about PAS. Unlike some countries in the West (such as the Netherlands and Belgium), China has not embraced this concept as yet. For me, a retired Chinese-born American physician and a Christian minister and chaplain, my heart goes out to these patients. At the same time, I often wonder if I can truly understand the Chinese perspective on suffering and “good death.” What would it mean to the terminally ill and their families as well as their caregivers to live through this ordeal in China? What sustains them, and what are their reasons for living? How can chaplains and other caregivers best support them?

Thesis and Flow of Argument

When I see these terminally ill patients suffering from unimaginable pain physically, emotionally and financially, I ask myself the same question many times: What is it that prompts many of these tormented people to choose life, instead of killing themselves? It is the same question that Viktor Frankl asked while confined in the Auschwitz concentration camp. He found the answer in “will to meaning,” which sustains the lives of his fellow inmates.[7] Building on this notion, I submit that hope may provide the terminally ill with a positive attitude to remain engaged in life even in the darkest of times. Hope allows one to project into the future for positive meaning in the present. I submit that when the terminally ill seriously consider suicide, hope may deter them from such an act. In the words of James Cone, the theologian, “Without hope, you die.” [8]

I argue that not only can hope rest in meaning[9] as an experiential process, it can also rest in: love and support[10] as a relational process; in faith and trust[11] as a spiritual or transcendent process; and in choosing realizable goals and attaining them[12] as a rational process. These dimensions of hope[13] appear to be uniquely suited to deal with the existential concerns that are commonly found in the terminally ill, namely meaninglessness, isolation, groundlessness, and death.[14] Hope has also been argued to be the first virtue (or human strength) that develops in the human life cycle.[15] To the extent that strengths build upon prior strengths, this means that hope is the basis for all other strengths.

Hope, as vision, also takes on differently colored lenses according to varying cultural and communal contexts. Chinese and Western perspectives on meaning and hope bring to light assumptions and presuppositions in both perspectives and each enriches the other. It is my fervent hope that the terminally ill, Chinese or otherwise, will benefit from this exchange of ideas and have access to more options to help them cope with their suffering and achieve a quality of life that they perceive as satisfying.[16]

Overall, this dissertation argues the following points: (1) building on Viktor Frankl’s will to meaning, and the unique characteristics of hope (including its widespread significance, spiritual implications, and relational and rational nature), I submit that hope can provide the terminally ill with a positive attitude to remain engaged in life even in the darkest of times, making suicide less of an issue; (2) hope is uniquely equipped to deal with the existential concerns of the terminally ill, resting in meaningful experiences, trust and love, faith and spirituality as well as rational thoughts and actions; (3) hope is not something that can be given to or imposed on the cared-for, but an attitude or virtue that can be fostered in and reinforced by the cared-for through practice; (4) the one-caring can infuse a sense of hopefulness into the caring environment through an unwavering commitment to caring for the other person; and (5) fostering hope needs to take into consideration the cultural and communal settings of the cared-for.

Research Methods

The primary method used in this research is literature review and critical analysis. Research interviews were conducted to supplement this literature analysis. The research question I had in mind was two-fold: (1) when the poor with terminal illness in China cannot afford their medical care and get adequate pain relief, what is life like for them and their family caregivers, and (2) what role can be played by the family and professional caregivers to meet some of their needs? In relation to both questions, I was especially interested in the value of hope. My field work in China consisted of research interviews that investigated the experience of living through terminal illness in China and identified, through literature review, the means of relevant spiritual care for suffering, for finding life’s meaning, for existential concerns, and for fostering hope.

Through personal contacts and professional relationships with patients, physicians, spiritual caregivers and counselors in Southern China, the author interviewed twenty-three individuals in China during the period October 2007 to January 2008. Fifteen of them were afflicted with terminal illness, five were related family members, and three were spiritual counselors (one Taoist priest, one Buddhist physician, and one Imam). In these interviews, only open-ended questions were asked in order to encourage the interviewees to tell their stories. Closed questions that would elicit only “yes” or “no” answers were avoided. Any reference to hope by the interviewer was implicit. Generally, three questions were posed: (1) Can you describe your understanding of suffering? What does it mean to you? (2) What would be your experience with this illness that has affected you (or your family)? (3) How would you (or your family) view life and death when dealing with this illness? Special attention was paid to causal factors, intervening factors and contextual factors that affect suffering, and to the coping strategies as well as consequences. After each interview, short notes were written within an hour, and a summary of each interview was typed out within twenty-four hours. Statements from each interviewee were quoted as faithfully as possible (see Appendix). Some of the stories and comments I heard in this field work are used throughout the dissertation to illustrate, where appropriate, pertinent points brought out by the literature on meaning of life and hope, bringing together Chinese and Western resources on helping these people live through terminal illness.

It should be pointed out at the onset that these research interviews were not conducted according to formal empirical standards. My argument regarding hope in the terminally ill remains untested empirically. Such research work in the future might better establish its validity. The rigorous standards of empirical research were not employed for the interviews, because the Chinese Government is resistant to any research project seen as religious. Officially, religious organizations in China today must be Government-recognized and approved. The three state-endorsed religious organizations are the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association, the Three-Self Patriotic Movement for Protestants,[17] and the Chinese Patriotic Islamic Association. Buddhism and Taoism are the two other religions officially recognized by the state. Confucianism is considered as a philosophy and not a religion in China.

References:

[1] Spiritual care is defined here as care that encourages and supports the cared-for’s own reflections on experience, search for meaning and purpose, and development of inner resources for the spiritual journey.

[2] Suffering is defined here as distress that arises from an individual’s perception of pain.

[3] Terminal illness is defined here as an active and progressive disease that cannot be cured or adequately treated and which is expected to lead to the eventual death of the patient.

[4] The Hippocratic Oath I follow as a physician says in part, “I will not give a lethal drug to anyone if I am asked, nor will I advise such a plan.” The National Institutes of Health’s History of Medicine Division provides a full text of the Hippocratic Oath on its website. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/greek_oath. html (accessed May 20, 2008).

[5] Hope is defined by Erik H. Erikson as “an attitude, an enduring belief in the attainability of fervent wishes” in “Human Strength and the Cycle of Generation,” Insight and Responsibility (New York: W. W. Norton, 1964), 118.

[6] This phrase first appeared, as far as I know, in the title of an article by Robert L. Richardson, “Where There is Hope, There is Life: Toward a Biology of Hope,” Journal of Pastoral Care 54, no. 1 (Spring 2000), 75-83. Life refers to the quality that distinguishes a vital and functional being from a dead body (Merriam-Webster Dictionary).

[7] Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy, rev. and trans. Ilse Lasch, rev. and enl. ed. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1962), 113.

[8] Quoted in an article in the March 19, 2008 edition of Newsweek. http:// www.Newsweek/ Washingtonpost.com (accessed May 20, 2008).

[9] Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning,105.

[10] Gabriel Marcel, as related by Jean Nowotny, “Despair and the Object of Hope,” in The Sources of Hope, ed. Ross Fitzgerald (Rushcutters Bay, Australia: Pergamon Press, 1979), 66.

[11] Paul W. Pruyser, Between Belief and Unbelief (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), 198-213.

[12] Erik H. Erikson, “Human Strength and the Cycle of Generations,” Insight and Responsibility (New York: W. W. Norton, 1964), 117.

[13] Carol J. Farran, Kaye A. Herth, and Judith M. Popovich, Hope and Hopelessness: Critical Clinical Concepts (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995), 6.

[14] Irvin Yalom, Existential Psychotherapy (New York: Basic Books, 1980), 8.

[15] Erikson, “Human Strength and the Cycle of Generations,” 115.

[16] Quality of life is defined by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, Georgia) as an overall sense of well-being with a strong relation to a person’s health perceptions and ability to function.

[17] This Movement is characterized by self-governance, self-support (without financial dependence on foreigners) and self-propagation.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1. Health Care in China

Overview

Economic and Social Change

Demographic Change

Medical Need among the Elderly

China’s Strategy in Managing Transition

Evolution of Health Care in China

The Period Between 1949 and l965

The Period of the Great Cultural Revolution 1965 – 1978

Problems of the Traditional Health Care System

Health Care Reform (from 1980s)

Emergence of Basic Health Insurance (urban)

Reform in Cooperative Health Care (rural)

Current Management of Health Care

Fiscal Decentralization

Financial Responsibility System

Government’s Price Reform

Evaluation of Health Care Reform since 1978

Overall functioning of China’s health care delivery system

Disparities between China’s Rural and Urban Areas

Equity in Accessing China’s Health Care

Summary

Chapter 2. Living Through Terminal Illness in China

Living Through Terminal Illness in China

Chinese Perspectives on Suffering

Chinese Cultural Beliefs

Uncontrollability

Ubiquity of Change

Fatalism

Dualism

Collectivism

Utility of Efforts

Strengths and Virtues in Coping

Chinese Perspectives on Life and Meaning of Life

Chinese Perspectives on “Good Death”

Chapter 3. Western Philosophical Perspectives on Meaning of Life

Western Philosophical Perspectives on Meaning of Life

True-World Philosophy

Continental Philosophy

Quality of Life

Search for Existential Meaning

Critique and Discussion

Implications for the Terminally Ill

Chapter 4. Hope

What is Hope?

The Earliest Virtue

Development of Hope

Chinese Perspectives on Hope

Western Perspectives on Hope

Four Dimensions of Hope

Christian Theology of Hope

Grounding in Scripture

Contemporary Theology of Hope

Critique

Pastoral Theology of Hope

Summary and Discussion

Chapter 5. Is Fostering Hope Justified in the Terminally Ill?

Ethical Consideration

Existential Consideration

Meaninglessness and Hopefulness

Isolation and Hopefulness

Groundlessness and Hopefulness

Death and Hopefulness

Research Consideration

Biology of Hope

Chapter 6. Fostering Hope in the Terminally Ill

General Considerations

Cultural Considerations

Role of Physicians

Role of Hospice Programs

Role of Pastoral Caregivers

Where there is Hope, there is Life

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the expertise provided by Professor Kathleen Greider, Professor Ellen Marshall, Professor Samuel Lee from Claremont School of Theology (CST) in the preparation of these manuscripts. In addition, without the scholarships provided by Professor William Clements and the Chinese Baptist Church of Orange County, this dissertation would not have been possible. Throughout these many years of study, my wife Rosangela has stood by my side, providing every possible help that I need. To all these wonderful people I express my sincere gratitude.

CHAPTER 1: Health Care in China

Overvie China is in transition. She is in transition from a command economy to a market economy; from a rural society to an urbanized and industrialized society; and from isolation to welcoming the whole world in the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. Communication is rapidly expanding within the country and with the rest of the world. Together with the other transitions, the age structure and medical needs of her citizens are also in transition. While China is now the fastest growing economy in the world, her torrid economic growth has been uneven, leading to a wider gap between the rich and the poor. Such discrepancy can be reflected in the health care sector today.

According to official statistics, China is still a largely rural society. However, over the past 20 years the proportion categorized as urban has grown sharply. In the year 2000, 458 million people were registered as permanent residents of urban areas, or 36.2% of the total population (see Table 1).

Table 1: Trend in urban population growth, 1980-2000

| Year | Total population in millions | Urban population in millions | Proportion in percentage |

| 1980 | 987 | 191 | 19.4 |

| 1985 | 1059 | 251 | 23.7 |

| 1990 | 1143 | 302 | 26.4 |

| 1995 | 1211 | 352 | 29.0 |

| 2000 | 1266 | 458 | 36.2 |

In 1980, there were 223 cities, of which 15 had more than a million people.

Twenty years later there were 663 cities, of which 41 were bigger than a million (see Table 2).[1] These changes are due to a combination of in-migration and the re-classification of areas from rural to urban.

Table 2: Number of cities by size of non-agricultural population

| City size | 1980 | 1991 | 2000 |

| 2 million + | 7 | 9 | 14 |

| 1-2 million | 8 | 22 | 27 |

| 0.5-1.0 million | 30 | 30 | 53 |

| 0.2-0.5 million | 72 | 121 | 218 |

| less than 0.2 million | 106 | 297 | 352 |

| Total | 223 | 479 | 663 |

Classification of a household as urban or rural greatly affects its entitlements.

Registration status has important implications for a household’s ability to obtain employment and secure social benefits. Officially sanctioned rural-to-urban migration requires a formal household registration or hukou transfer from agricultural to non-agricultural status. Without this registration, these migrants would have difficulty securing employment and health care benefits in the urban area. Rural-to-urban migrants now constitute an important, but unknown, proportion of urban residents.

Economic and Social Changes

China has experienced more than 20 years of sustained economic growth which has led to rapid rises in average annual disposable income per capita, rising from CNY343 (Chinese Yuan) in 1978 to CNY6,280 (under USD1,000) in 2000.[2] This has been associated with changes in patterns of consumption. One sign of the pace of change is the increase in the number of color television sets per 100 households in urban areas from 17.2 to 116.6 between 1985 and 2000. Even the poorest 10 per cent of urban households had 99 sets per 100 households. Television reached 93.7% of China’s population in 2000. This provides an indication of the rapid growth in communication that has accompanied economic growth. Many goods and services, including health-related ones, are now advertised on television, radio and in print media. This has influenced popular expectations.

However, economic growth has not been distributed evenly. The eastern parts of the country have developed much more quickly than the west. In 2000, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita ranged from CNY2,662 in Guizhou (in south-western China) to CNY22,460 in Beijing.[3] In addition, there are substantial differences in the economic well-being of households within each locality. In 2000 the poorest 10% of urban households had an annual income of CNY2,678 per capita, compared with CNY13,390 for the richest 10%.[4] These substantial inequalities have a number of effects. On the one hand, the patterns of consumption of the richer groups influence overall expectations of life styles.

In recent years, a group of urban poor has emerged, which includes the unemployed, the under-employed, the disabled, the retirees, and those who were laid off. The growing economic inequality is largely associated with increasing diversity in types of employment. In 1980, most urban jobs were in state- or collectively-owned enterprises. In 2000, employment in the first two categories had fallen, while a larger number of people (12.7 million compared to 4.9 million in 1995) worked for privately-owned companies. Over 20 million people were self-employed (see Table 3 below):

Table 3: Number of employed people (in millions) in urban areas by type of employee

1980 1985 1990 1995 2000

| State-owned enterprises SOEs | 80.2 | 89.9 | 103.5 | 112.6 | 81.0 |

| Collectively-owned enterprises Collectively-owned enterprises | 24.3 | 33.2 | 35.5 | 31.5 | 15.0 |

| Privately owned companies | — | — | 0.6 | 4.9 | 12.7 |

| Self-employed | 0.8 | 4.5 | 6.1 | 15.6 | 21.4 |

In the mid-1980s, the government introduced labor contract system to replace the previous guarantees of “work until retirement” in state-owned enterprises (SOEs), making it possible to lay off workers when these SOEs became unprofitable. Thus, even though the registered unemployment rate in urban areas has been consistently quoted as 3.1% since 1997 according to national statistics,[6] the real unemployment rate was found to be 6.99%

in 1999, when the number of laid-off persons was taken into account.[7] Even though women did not make up a disproportionate share of the total numbers of laid-off, their unemployment rate, as related to their total employment, was higher than men, since they made up less than half of the workforce. These laid-off workers, together with the other unemployed and disabled, constitute the urban “poor and vulnerable” at the very bottom of the social scale.[8]

The government has defined minimum living standards for urban areas, below which people are entitled to financial support. According to a survey by the Ministry of Civil Affairs, which oversees the “poor and vulnerable,” around 14 million urban residents had an income below the local poverty line in 2000, varying from CNY1,680 to CNY3,828 on average per person according to the city. Poverty lines reflect differences in the cost of living and in the capacity of city governments to pay income supplements. Also, poverty lines for residents of “rural” counties within municipal boundaries are actually much lower than the average quoted. In addition, many more people have incomes just above the poverty line. This suggests that quite large numbers of people are poor or at risk of impoverishment. This has important implications for health care.

Demographic Change

The age structure of China’s population is also changing rapidly. An active family planning policy and factors associated with economic and social development, together with rising average life expectancy have led to a fall in the proportion of young people (below the age of 15 years) and a rise in the proportion of elderly (65 and over). The proportion over 65 years grew from 3.6% in 1964 to 7.0% in 2000 (See Table 4 below). The proportion over 75 years old more than doubled from 0.8% in 1964 to 2.2% in 2000. This aging of the population is expected to continue and have a significant impact on the future health care system in China.

Table 4: Age structure of China from 1964 to 2000 [9]

| Age (in years) | 1964 (%) | 1982 (%) | 1990 (%) | 2000 (%) |

| 0-14 | 40.7 | 33.6 | 27.7 | 22.9 |

| 15-64 | 55.7 | 61.5 | 66.7 | 70.1 |

| 65+ | 3.6 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 7.0 |

| 75+ | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.2 |

Medical Need among the Elderly

Medical need has been defined as the existence of ill-health for which an effective treatment is available.[10] The extent of medical need is a measure of the physiological and psychological well-being of individuals; their expectations of what constitutes well-being; the availability of effective interventions; and the social arrangements that determine the roles of households and health providers in caring for the sick. According to this definition, medical need is determined by the burden of sickness and the social consensus about the kinds of support sick individuals require. Both determinants are changing in China, it seems.

The aged account for a substantial share of medical care costs in urban China. Data from advanced market economies suggest that average medical care costs rise rapidly with age.[11] Those over 75 years old have a particularly great need for expensive health care.

One reason for this is because of the nature of the diseases affecting the elderly, who have a prevalence of cardiovascular diseases and cancer, as well as chronic illnesses.[12] Another reason for the high cost is because of changes to family structures which have made family members less able and less willing to care for their sick relatives at home.[13] The lack of affordable medical support for the aged puts a heavy burden on family caregivers, particularly women, who stay home while men go out to work.

China’s Strategy in Managing Transition

China’s strategy in managing her economic transition is highly decentralized.[14] On the revenue side, each level of government can collect taxes. It retains most of the taxes and transfers some to higher levels according to complex and changing rules. In addition, county or city governments may also have substantial sources of revenue in addition to taxes. Many own enterprises that pay profits or management fees. Some also own land and collect ground rent. With this revenue, the local governments can have a great deal of autonomy in deciding how to use it. They can use this “extra-budgetary revenue” as they wish. Under this fiscal decentralization, local governments can, since the early 1980s, decide how much money or how big a grant to allocate to support health care facilities in their localities. The Ministry of Health has delegated this authority to them while maintaining only a supervisory relationship with the levels of government below it.

This fiscal decentralization has had two important consequences. It has led to growing differences in the resources available to local governments: some have very substantial revenues and others can barely pay salaries. It has also given local governments a lot of control over their own resources, and has limited the capacity of higher levels of government to do so.

It is important to note that the Chinese government is organized in a number of vertical structures that extend from national to local administrative levels. Each level of local government more or less replicates the structure at national level. For instance, each level of district/county and higher local government has a health department which is answerable to the government at the same level and to the health department of the next higher level. At each level, there are hospitals, preventive services, medical institutions, and health training schools, a majority of which are directly supervised by the corresponding health department. Such organization into parallel vertical channels has advantages and disadvantages. It has established close accountability, resulting in very effective preventive health programs at the grass roots. Furthermore, the close accountability makes it less likely for government health facilities to treat their own healthcare providers with favoritism. However, this system ends up having numerous commissions, ministries, and bureaus/agencies that have health-related mandates for planning, service provision, regulation and accountability, as well as financing.

In Table 5 below, it can be seen how this high degree of bureaucracy makes it difficult to formulate coherent healthcare development strategies and creates a nightmare in coordination. It is the Ministry of Civil Affairs and the civil affairs departments at provincial and lower levels that provide the safety nets for the poor and vulnerable.

Table 5: Government Organizations with an Influence on Health Care for the Poor and the Vulnerable [15]

For Planning – The State Development Planning Commission oversees the formulation of health care policies. It is also responsible for the implementation of five-year regional health plans.

For Service Provision, Finance, Regulation and Accountability – The Ministry of Health, under the authority of the State Council (which also oversees other reforms beside health reform, including economic and social reforms), provides overall leadership to the health sector. It is responsible for the performance of health institutions; provides annual grants to government health facilities (including public health); contributes to local health insurance schemes for government employees; and regulates all government health facilities as well as private healthcare providers.

For Regulation and Accountability – other bureau and ministries:

- The Price Bureau of State Development Planning Commission sets prices for health services and health-related commodities. There are similar price bureaus at the provincial, county, and municipal levels.

- The Ministry of Personnel manages civil servants as well as skilled workers in public employment.

- The Ministry of Labor and Social Security manages semi-skilled and unskilled laborers in public employment. This office was set up in 1997 to develop the Social Security system in China. It also sets up the Urban Basic Health Insurance.

- The State Drug Administrative Bureau was set up to develop drug-related regulations, approve the use of new drugs, and monitor the effective and safe use of all drugs in China. Initially the Bureau was established within the Ministry of Health, but has now become an independent government agency. At the provincial and lower levels, respective bureaus responsible for drug administration were also set up to carry out the same functions.

For Financing – beside Ministry of Health and Ministry of Labor and Social Security:

- The Ministry of Civil Affairs and the civil affairs departments at provincial and lower levels provide the safety nets for the poor and vulnerable.

So far, we have seen how China manages the health care of her people through a highly decentralized fiscal policy as well as a highly bureaucratic system of government. There are pros and cons in each of these as mentioned earlier. How successful have they been in responding to the health care needs of the Chinese people? Let us now take a look at the evolution of health care in modern China from the founding of the People’s Republic to the present time.

Evolution of Health Care in China

The history of health care in modern China can be generally divided into three periods: (1) from the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949 to the eve of the Great Cultural Revolution in 1965; (2) the years in which the Great Cultural Revolution was taking place (1966-77); and (3) from the beginning of the economic reform in 1978 to the present.

The Period Between 1949 and l965

When the People’s Republic of China was established by the Chinese Communist Party in 1949, the country had inherited a poorly developed health sector.[16] The major medical care providers were Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practitioners who used a combination of herbal medicine, acupuncture and other traditional methods to treat patients. The relatively small number of doctors of Western medicine worked mainly in the urban hospitals.

In 1951 the First National Health Conferences sponsored by the State Council of the new government was held and the following health policies were announced:[17]

- Medicine must serve the working people (workers, peasants and soldiers)

- Preventive programs must be given priority over curative care

- Health services must integrate the services of practitioners of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Western medicine

- Health care must be integrated with mass movements

From the early 1950s to 1965, before the beginning of the Great Cultural Revolution, existing facilities were renovated and new “people’s hospitals” and other preventive health facilities were built in each city and urban district. Some industrial sectors, such as mining, railways and telecommunications, and military organizations established their own hospitals, numbering around 1,500 by 1965.[18] Most of these hospitals were located in the urban areas, serving the employees and dependents of these industries. In addition, almost every government institution, enterprise and school had a health clinic which provided very basic curative and preventive services. Paramedics were trained to serve at community clinics, acting as the first-line providers of health services. Thus, the network of urban health services was greatly expanded.

Training capacity also expanded rapidly over the period. The number of graduates of medical and pharmacy schools grew from 1,314 in 1949 to 22,027 in 1965. As a result, the number of doctors of Western medicine in China increased fivefold and the number of pharmacists rose from virtually zero to 8,000 in 1965.[19] Most of the doctors and pharmacists were employed by the urban hospitals and other urban health facilities, although efforts were made by the government to deploy more health professionals in the countryside.

It should be noted that, during the 1950s and early 1960s, the development of healthcare services in urban China mainly followed the model adopted by the former Soviet Union before friendship between China and the Soviet Union ended. The majority of urban residents who were employed were covered by a traditional health care system that was implemented in the 1950s and continued right up to the mid-1990s when health reform was carried out. Specifically, this traditional health care system was administered through two insurance schemes: (1) the government-funded insurance scheme (GIS) for personnel of government agencies and institutions, including disabled veterans; and (2) the labor insurance scheme (LIS) for state-owned enterprise (SOE) staff and workers. These SOEs were enterprises of more than 100 workers each, including factories and enterprises in the railway, mining, transport, and postal industries. Insured employees virtually enjoyed free health care for work-related and non-work-related illnesses, injuries, and disabilities. They only had to pay for expensive medications. Immediate family would have half of the medical expenses for surgery and general medicines paid for by the SOE. Under a command economy with such employment-based benefits, there was significant improvement in the health of the vast majority of Chinese urban population.

In contrast, health care in the rural area was administered through the Cooperative Health Care System launched by local farmers in the mid-1950s, and subsequently affirmed by the central government.[20] Under this system, a health care fund was set up with contributions from members of a production team or commune as well as subsidies directly provided by the production team or commune. Members received medical treatment or prescriptions free or at reduced price. However, there was only limited number of healthcare providers available in the rural area, based in small clinics at the township and county levels.

This bi-furcated health care system has created regional inequality between the urban and rural populations. Whereas the urban employed could enjoy the traditional health care available in the cities, access to basic health care remained inadequate for most of the rural population in China.

The Period of the Great Cultural Revolution 1965 – 1978

In 1965 Chairman Mao made a famous speech criticizing the health sector for favoring the urban areas and calling for a radical change in priorities. At almost the same time, Mao and his political allies within the Communist Party Committee of China launched the Great Cultural Revolution, which brought political and economic turbulence to China over the following decade.

The new Ministry of Health began to make rural health development its priority policy. This resulted in the training of large numbers of “barefoot doctors” – part-farmers and part-doctors – to play a key role in the provision of rural health care, the construction of rural health facilities, and the re-organization of rural cooperatives to provide funds for rural health services.

An important goal during the Great Cultural Revolution was reduction of the inequality between urban and rural areas in the numbers of available health care workers. Many training and research centers in the urban areas were closed. High-level medical education was restructured. The five-year training program for medical and public health doctors was reduced to three years. Many doctors from urban hospitals were sent to the countryside to provide the rural residents with better health care and to supervise poorly trained rural health care workers. For example, in 1969, Gansu Province in western China sent 50% of its urban doctors to rural health facilities.[21] At the same time, new medical and public health graduates were automatically assigned to rural facilities. The number of qualified doctors in rural areas was almost doubled within ten years, while the number of nurses in rural areas increased by 137%. In addition, the construction of health care facilities in the rural areas overshadowed the urban sector. By 1975 over 85% of villages in the rural areas had a health station. By 1976, about 90% of the rural residents in the country had enrolled in the Cooperative Health Care System.[22]

In summary, the outcomes of the health sector emerging from the Great Cultural Revolution were mixed. On the one hand, the overall quality of health care in many cities deteriorated because of the collapse of the urban medical referral system involving clinics and hospitals. In addition, many health institutions, including medical or pharmacy schools, were unable to function effectively, with deleterious effects on education and research. On the other hand, the health status of the rural population in China improved dramatically, resulting from, among others, the deployment of qualified doctors, the training of “barefoot doctors,” and the further development of rural Cooperative Health Care System.

Problems of the Traditional Health Care System.[23] Under the traditional healthcare system, workers who were covered by either the government or labor insurance schemes (GIS/LIS) were provided with a relatively decent level of health care, including free diagnosis and treatment, general medicines, and surgery. In a command economy, this system guaranteed the majority of urban residents basic health care, thereby fostering social stability and economic development. However, as a result of the decollectivization of the rural economy, decentralization of decision making, introduction of management accountability, and emergence of the private sector, problems of this traditional health care system began to surface in the late 1970s.

First, there was little control over the provision and consumption of healthcare services, resulting in high medical costs, low efficiency, and tremendous waste.[24] It was estimated that about 20-30 percent of total medical costs was considered medically unnecessary. On the demand side, there was excessive use by the consumers. On the supply side, since hospitals, receiving less and less financial support from the local government, had to rely on profits from the use of high-end medical equipment and the sale of medicines to defray operating expenses,[25] many hospital-based physicians ordered unnecessary diagnostic tests or over-prescribed medicines to increase hospital incomes, thus further increasing the medical cost. Second, the broad range of medical benefits at little or no cost to workers had drained both government and enterprise treasuries.[26] Third, since health care was tied to employment and there was a discrepancy in the level of medical services received by workers employed by various enterprises, the resulting low labor mobility in turn slowed down the development of a labor market. Fourth, there was no attempt by these enterprises to pool their risks and their funds to pay for the medical expenses of their workers.[27] When enterprises experienced financial difficulties, they either contracted a low volume of health care or were in arrears with reimbursements for medical fees. Therefore, many workers did not receive the basic health care to which they were entitled. Fifth, even though private enterprises and foreign investment enterprises had developed rapidly, workers in those enterprises were not able to enjoy even basic health care.[28] In summary, the traditional healthcare system (GIS and LIS) oriented toward the urban employed resulted in high medical costs; imposed a heavy financial burden on the state treasury and enterprises; hindered labor mobility; had a low capacity to resist risk; and benefited only certain segments of society.

On the rural side, with the de-collectivization of the rural economy, and the disintegration of rural communes, the Cooperative Health Care System broke down and left the rural population stranded. This set the stage for health care reform following Deng Xiao Ping’s economic reform in 1978.

Health Care Reform (from 1980s)

Starting from the 1980s, local health authorities and enterprises began to undertake measures to reform the health care system.[29] (1) Workers were required to share with their employers part of their medical costs, normally 10 to 20 percent, with an upper limit set for out-of-pocket payment. (2) A capitation system was introduced, in which enterprises gave health care providers a fixed sum of money annually for taking care of a certain number of employees.[30] (3) In 1989, some municipalities began to set up social pooling funds to cover the medical cost of retirees, [31] while others launched pooling funds for serious illnesses. (4) In 1993, personal medical account was added to the socially pooled funds to help workers save for future medical needs.[32] However, all these reform measures were still undertaken within the framework of the traditional health care system, but did little for the masses.[33]

Emergence of Basic Health Insurance (urban). Over the years, China has adopted an incremental approach to effect reforms in various respects, such as economic reforms and labor reforms. Health care reform is no exception. In 1996, a national conference on Basic Health Insurance was sponsored by the State Council. As a result of that conference, over fifty cities became test sites of this health care reform, incorporating the above-mentioned features into the trial scheme.[34] Encouraged by the results, the State Council promulgated a landmark decree in December 1998, the “Decision concerning the Establishment of the Basic Health Insurance System for Urban Staff and Workers,” followed by the unification of the government insurance scheme (GIS) and the labor insurance scheme (LIS) in 1999 to form the “Basic Health Insurance System for Urban Staff and Workers” (in short, Basic Health Insurance). Its slogan is “low level, broad coverage.”[35] The underlying objective of this health care reform is to provide better-quality medical services at relatively cheap cost in order to satisfy the basic medical needs of the urban employed.

The general framework of this insurance is composed of a socially pooled fund and personal medical accounts, to be managed by the Social Security administration of the local government rather than by the employers. The socially pooled fund is drawn from the insurance premium paid by the employers and employees, while the personal medical accounts are designed to encourage employees to save for their future medical needs and to control waste resulting from excessive usage of medical services. Thus, the cost of medical care is to be shared between employers and employees.

Under this Basic Health Insurance, workers go to designated healthcare providers for diagnosis and treatment. Thereafter, they can fill prescriptions at the hospital’s outpatient pharmacy or at designated drug retailers. Designated health care providers are certified by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security and must sign capitation contracts with the social security administration of the local government in order to provide medical services.

This Basic Health Insurance is meant to cover all urban workers employed in enterprises, institutions, and government organs nationwide. To ensure fairness and to bring into play the initiative of workers, those who have made a significant contribution to society can have the extra benefits of a supplemental insurance from the government or state-owned enterprise. This supplemental insurance can also be offered to those who are suffering from serious illnesses. Commercial insurance is also available for those who can afford it through their employers. Unfortunately, for the unemployed, the disabled, and those who have used up all the funds from available insurance channels, medical relief is the last resort for those under the poverty line.

This health care reform consists of two other major components beside the Basic Health Insurance: the reform of medical establishments, and the reform of the medicine production and circulation system. For the purpose of this paper, I will not go into details on these two reforms, suffice it to say that

- quality and efficiency of medical personnel are to be increased, and their total number is to be decreased

- fee schedule of medical services is to be normalized

- access to health care is to be improved by actively developing community health services and incorporating these services into the coverage of the Basic Health Insurance

- medications are separately managed from medical services

- health care providers are discouraged from over-prescribing medications by setting a limit to the proportion of hospital income from filling prescriptions to the total income of each medical establishment

- centralized solicitations of bids from drug wholesalers are to be encouraged

- the franchising of retail drugstores and counters for nonprescription drugs in franchise shops and supermarkets are to be encouraged; hospital pharmacies are expected to be eventually converted into independent retail drugstores

- drug prices are to be normalized nationally, with the government setting the prices of designated medicines, listed under the formulary of Basic Health Insurance, for which patients can get re-imbursements

- the retail price of a medicine has to be printed on its packaging to prevent price gouging, while invoices based on the actual price of a medicine must be produced at every stage of sale

There are some notable changes in this healthcare reform. First, health care is now treated like an industry. The administrative-subordinate relationship between the Ministry of Health and hospitals is abolished, with the former now serving the supervisory role and the latter serving the technical-service role. Formerly, the Ministry of Health managed hospitals. From now on, the Ministry of Health only supervises medical establishments at the industry level. Second, medical establishments are now classified as for-profit and not-for-profit, with the latter receiving preferential tax treatment. For-profit medical establishments may set their own fee schedule, but must pay tax in accordance with the law. Some not-for-profit medical establishments are run by the government and receive subsidies from it. Third, there is now an extensive service system of community health centers, general hospitals, and specialized hospitals. Conversion, cooperation, merger, and grouping of hospitals are encouraged, so as to secure the rational distribution and utilization of medical resources.

As a result of this reform and the ensuing competition, the management level of hospital leadership, the doctors’ consciousness regarding medical expenses, and the quality of hospital services have improved.[36] Moreover, hospitals have either streamlined their operations or merged with others to remain competitive.

Reform in Cooperative Health Care (rural). Along with the reform of the urban health care system and the de-collectivization of the rural economy, the old Cooperative Health Care System supported by communes and production teams needed to be revised. The problem was a pressing one: China has 900 million rural people, and more than 700 million remain in the countryside and live in poor conditions.[37] In 2003, the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Agriculture jointly promulgated the “Circular concerning the Establishment of a New-Style Rural Cooperative Health Care System.”[38] According to this circular, the New-Style Cooperative Health Care System is to be organized, guided, and supported by the government; funded from various channels (including the central and local governments plus various cooperative entities in the countryside); and enrolled in voluntarily by individuals.

Under this pooling scheme, each farmer is to pay at least 10 Yuan a year (USD1.25) into his/her personal medical care account as an insurance premium, and the collective economic entities in villages plus the government (local and central) will inject another 40 Yuan (USD5) into this account. Then, the government will pay a maximum of 65% of his/her medical charges a year. Localities with better economic conditions may raise the amount of premium. As for workers employed by township and village enterprises, the county government will decide whether they should participate in the Basic Health Insurance or the New-Style Cooperative Health Care System (called New Cooperative from here on).

The fund from this New Cooperative is used primarily for large medical expenses and hospitalization charges. If, in a given year, an enrollee has not used any money from the fund, a regular physical checkup is allowed, to be paid out of this New Cooperative fund. It is the local county government that will determine the fee schedule and what examination items are appropriate for this regular checkup. The charges incurred on medications are determined from a list set up by the provincial government or equivalent.

Starting in 2003, each province, autonomous region, and municipality directly under the central government must select at least two to three counties (or cities) as test sites for this reform, and, after gaining the necessary experiences, gradually expand this rural healthcare reform to other counties. Any county that cannot fulfill such requirement may still coordinate its villages (or townships) in the initial stage of implementing the new system. The ultimate goal is to have the New Cooperative implemented nationwide by 2010.

Thus, in a nutshell, the Chinese system of health insurance is pluralistic and multi-layered. It is pluralistic because several sources together fund the overall health insurance scheme – government, enterprises, workers, and donations. It is multi-layered because the means of payment for medical costs consist of various levels: individual savings (personal medical account and personal funds), family assistance (supplemental), a socially pooled or cooperative fund under unified collection and management of premium (mutual aid among enterprises, institutions, and cooperative entities), enterprise insurance (supplemental), commercial insurance (supplemental), and medical relief (for people under the poverty line).

There are two major reasons for such a pluralistic and multi-layered health insurance scheme. First, since the socially pooled fund covers only the basic medical services, there is plenty of room for developing other types of insurance due to differences in income level and medical needs. Second, it is recommended that regions, industries, and enterprises that used to provide medical services above the basic level establish multi-layered health insurance, thereby guaranteeing the connection of the old and new systems as well as the steady implementation of medical reform.

By the end of 2002, about 69.26 million workers and 24.74 million retirees had subscribed to the Basic Health Insurance.[39] The increasing number of subscribers demonstrates that the implementation of the Basic Health Insurance has gained full momentum. As for the New Cooperative, it is still too early to evaluate its impact. Because of its modest funding,this New Cooperative covers only inpatient care (with a very high deductible)and leaves farmers without adequate primary care services anddrug coverage.

Current Management of Health Care Facilities

Fiscal Decentralization

For most local governments in China, the development of health care has not been a priority over the past two decades. Developing the local economy has always been given a higher priority than health care and other social services. As a result of fiscal decentralization, the proportion of income from government to hospital finance has declined significantly since the economic reform started in the 1980s. It accounted for only 8.7% on average of hospital revenues in 2000 (see Table 5 below which provides a clear picture of how sources of hospital income have changed over the past two decades).

Table 6: The composition of hospital incomes in China, 1980-2000 [40]

Items 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000

| Total income (CNY100 mill.) | 292.6 | 428.6 | 702.2 | 1,003.4 | 2,296.5 |

| % of medical service | 18.9 | 22.2 | 28.6 | 34.7 | 40.2 |

| % of drugs | 37.7 | 39.1 | 43.1 | 49.8 | 47.1 |

| % of government subsidies | 21.4 | 20.2 | 11. 6 | 7.5 | 8.7 |

| % of other source | 22.1 | 18.6 | 16.7 | 7.9 | 4.0 |

Table 7: The Chinese Government’s Share of National Health Spending,as a Percentage of Total Health Care Expenditures

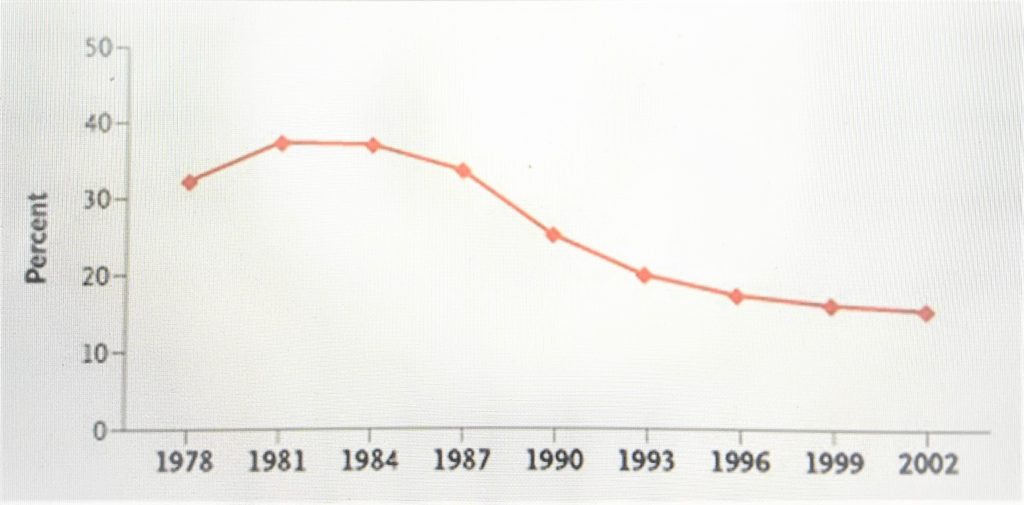

From 1978 to 1999, the central government’s share of national health care spending dropped from 32% to 15%.[41]

Financial Responsibility System

Consequently, with fiscal decentralization, hospitals and other health facilities are required to generate as much revenue as possible by charging higher medical service fees to patients in order to cover the increasing operational costs. In 2000, the percentage of hospital income due to medical services had increased significantly to 40.2%, with a significant drop in government subsidies (see Table 6).

Under the fiscal decentralization and the financial responsibility system, managers of these institutions have been given more autonomy in the management of their institutional (1) financial and (2) personnel affairs as well as (3) provision of health services.

Financially, if the health facilities have a surplus from their revenue-generation activities, the managers have the power to decide what proportion of the surplus can be used to pay bonuses and how much should be spent on investment for further development. With the support of their staff, they can set up a system that defines how bonuses should be paid to different levels or types of employee.

In personnel affairs, the health managers have a bigger say in the recruitment and firing of new staff. Increasingly, health professionals have been given job contracts instead of being offered permanent jobs as was the case previously. As a whole, human resource management in many health facilities has been improved greatly over the past two decades, but a lot remains to be done in order to improve the efficient use of health personnel.

In providing health services, health managers have often strategically developed new health services in order to generate more revenue and profits for their own facilities (e.g. through purchasing new high-tech imaging equipment). To some extent, the provision of care in many health facilities in China has been driven by profit, rather than the health service needs of the local population. The majority of district and higher-level hospitals in China have purchased CT scanners to make profits. One typical example is that the price of a CT (computerized tomogram) scan examination was once set at a level much higher than its cost.

In enhancing productivity, which has declined substantially due to increases in cost of health services and falls in utilization, managers of most hospitals have introduced an incentive system, which offers incentives for achieving revenue targets for departments, units and individual staff. The system developed in most hospitals was initially driven by a desire to increase revenue by encouraging doctors and other health professionals to increase utilization of medical services and sell more drugs to their patients. This means that the more revenue doctors generated from the provision of services or the sale of drugs, the more bonus they could get in their monthly pay. Such an incentive did increase labor productivity. However, over-prescription and overuse of high-tech diagnostic procedures and treatments have dramatically driven up the cost of medical care,[42] and made patients less trusting of their attending physicians. In recent years, these problems have been recognized and hence, some measures to improve the cost-effectiveness of services, including patient satisfaction, have been brought in to reverse the situation.

Government’s Price Reform

Before the economic reform, the prices of health services and drugs were set at a very low level by the government so that the vast majority of the population could afford them. The Chinese government started to reform the prices of health services from the early 1980s. The main purpose of the price reform was to let new higher prices reflect the real costs and enable health care providers to remain financially viable despite the limited financial support from government. Under these circumstances, a new health care pricing system was established for health services and pharmaceutical products. Provincial or municipal government agencies, led by the Price Bureau, establish higher fee schedules according to the local situation. All public health care providers and hospitals must follow the fee schedules issued by their local governments. In addition, public hospitals at and above county level are requested to self-monitor their pricing scheme.

Evaluation of Health Care Reform since 1978

This cascade of events – fiscal decentralization by the government, increasing financial responsibility of health care providers, and privatization of both enterprises and agricultural economy – can be best understood from the following three perspectives:[43] (1) the overall functioning of China’s health care delivery system; (2) disparities between China’s rural and urban areas; and (3) equity issue in accessing health care.

Overall Functioning of China’s Health Care Delivery System

In a 2001 survey of residents inthree representative Chinese provinces, half of the respondentssaid that they had forgone health care in the previous 12 monthsbecause of its cost.[44]In 2002, only 29 percent of Chinesepeople (urban and rural) have health insurance, and out-of-pocket expenses accounted for58 percent of health care spending in China as comparedwith 20 percent in 1978.[45] Yet, health care expenses are burgeoning, albeit from a lowerbase than in the United States. From 1978 to 2002, annual percapita spending on personal health services in China increasedby a factor of 40, from 11 to 442 Yuan (or from roughly USD1.35to 55). Overall, national spending on health care of all types(including public health) rose from 3.0 percent to nearly 5.5percent of the GDP. Because of the profitability of sellingpharmaceuticals and high-tech services, these items are widelyoverused. Half of Chinese health care spending is devoted todrugs (as compared with 10 percent in the United States).[46]Backed by Western capital, a new for-profit medical sector hasemerged to provide Western-style medicine in beautiful new facilitiesto China’s rich urban elite.In the meantime, the efficiency of the Chinese health care systemhas declined precipitously. With the growth of the private healthcare sector, the number of Chinese health care facilities andpersonnel has increased dramatically since 1980, but becauseof barriers to access, the use and thus productivity of thehealth care sector have declined.[47] To many in the United States,this portrait of pockets of medical affluence in the midst ofdeclining financial access and exploding costs and inefficiency may sound depressingly familiar. [48]

Disparities between China’s Rural and Urban Areas

In China’s market-based health care system, thewealth of consumers is a critical predictor of their accessto services and the quality of services, and with urban incomestriple the incomes in rural areas, urban residents have faredfar better than rural citizens. In 1999, 49% of urbanChinese had health insurance, as compared with 7% ofrural residents overall, and 3% in China’s poorest ruralWestern provinces.[49] Furthermore, the quality of care in ruralcommunities is inferior to that in urban communities for reasonsthat are familiar worldwide: the numbers and quality of healthcare facilities and personnel in rural areas are inadequate.In particular, rural communities depend on care from formerbarefoot doctors, who had little training and who now earntheir keep mostly by selling drugs and providing intravenousinfusions, a popular form of therapy for all kinds of problemsin China.[50] It has been estimated that one third of drugs dispensedin rural areas are counterfeit, enabling their vendors to earnhuge markups.[51]

Aware that their health care is poorer in quality, rural residents with serious illnesses frequently bypass local practitioners and facilities to seek care in the outpatient units of urban hospitals, leading to under-use of the former, overuse of the latter, and increased fiscal burdens on farmers who seek out more expensive, hospital-based services. Health expenses area leading cause of poverty in rural areas and a major reason that many migrate to cities seeking proximity to better health care facilities and higher wages to pay for care.[52] Regional differences in wealth also profoundly affect public health expenditures,which are more than seven times higher in Shanghai than in the poorest rural areas. [53]

These gaps in wealth, financial and physical access to care,and public health expenditures between urban and rural areasare reflected in health statistics. In 1999, infant mortalitywas 37 per 1000 live births in rural areas, as compared with11 per 1000 in urban areas. In 2002, the mortality rate amongchildren under five years of age was 39 per 1000 in rural areasand 14 per 1000 in urban locales. Urban and rural maternal mortalityrates in 2002 were 72 and 54, respectively, per 100,000. Perhapsmost shocking, in some poor rural areas, infant mortality hasincreased recently, although it has continued to fall in urbancenters, and there has been a resurgence of some infectiousdiseases, such as schistosomiasis, which was effectively controlledin the past.[54]

Gaps in health care are an important reason for growing angerin some rural districts toward the Chinese government, the ChineseCommunist Party, and China’s new, wealthy elite and they are contributingto increasingly frequent local riots and disturbances in ruralChina.[55] In a country where threats to established politicalauthority (such as the communist revolution itself) have sprungup for millennia from the grievances of an impoverished peasantry,the consequences of differentials between rural and urban healthcare carry profound political significance for the current Chineseleadership.

Equity in Accessing China’s Health Care

Equity has always been a critical issue to China’s health care system. Access to health care has primarily been based on employment – employment status, performance, and ownership of the employer – and the place of residence, i.e., the divide between rural and urban residence according to household registration. The traditional health care system, consisting of the Government Insurance Scheme (GIS) and the Labor Insurance Scheme (LIS), was designed for urban employees and was exclusive in coverage. The newly introduced Basic Health Insurance in 1998 continues this fundamental feature.

Despite these changes, the Chinese urban health care system is still characterized by the exclusion and inadequate protection of those who are uninsured and under-insured. For example, Zhuan identified five vulnerable groups in 2002 in Shanxi Province totaling two million workers or ex-workers of varying status, and a further 0.58 million of poor people, most of whom were old and chronically ill, who were covered by the government poverty relief program – with a certain guaranteed allowance for livelihood – but who had access problems to health care under the new Basic Health Insurance.[56] The five groups were: (1) employees of unprofitable enterprises; (2) unemployed workers; (3) retired workers on low pension benefits; (4) handicapped; and (5) rural-to-urban migrant workers. Apparently, all five groups were likely victims in terms of health care access because of their weak employment status in an open economy. It is worth noting that Shanxi Province had more urban poor than any other province in China at that time,[57] but the problem of health care access is not confined to Shanxi Province alone. It is a nation-wide problem. Even in Beijing, China’s capital, a similar situation has been reported. A survey conducted in 2001 by the Ministry of Civil Affairs, which is responsible for poverty relief and social welfare for the poor and vulnerable groups, revealed that three quarters of the respondents chose to treat their own illnesses without medical attention; three quarters paid out-of-pocket for their medical expenses; and only 12.2% had Basic Health Insurance.[58]

These findings should not be surprising because health care reform does not change the basis for health care system in China, which is based on employment. Even worse, economic reform has also brought about gaping differences in income. When China first reached the per capita GDP threshold of US$1,000 in 2003, many vulnerable groups were still underinsured or uninsured.[59] This is not to suggest that health care reform has not mitigated inequality in health care access at all, but there is evidence to suggest that lower socio-economic groups continue to be disadvantaged in their access to the type of health care they need when seriously ill.[60] While inroads have been made to improve equity horizontally in accessing basic health care, vertical inequity remains.

Summary

Healthcare services need to adapt to the changing patterns of need. The low birth rate has led to a fall in demand for maternal and child health services, while the aging of the population has generated unmet needs for a variety of support services. The growing number of urban poor and socially excluded people and the large rural-to-urban migration are also creating new needs. Healthcare institutions and facilities need to strengthen their capacity to monitor for, and respond to, new needs.

The Basic Health Insurance is the centerpiece of the government’s strategy for financing urban health services. The aim is to help establish this in all cities eventually. The richer cities could supplement this basic scheme. The challenge is to convince younger workers that they will ultimately benefit from it, or else they will see it as just another form of tax. This scheme currently does not cover family members of employees. This works to the detriment of middle-aged and elderly women, who are more likely to stay home rather than taking outside jobs. In addition, the present insurance scheme provides only partial benefits for out-patient treatment of chronic illness. This creates a heavy burden on some households and may in fact cost more in the long run because of the more expensive in-patient treatments.

Any health care reform is unlikely to succeed unless changes are made to the health care delivery system. The present heavy reliance on acute care hospitals for inpatient treatment and for the care of the chronic ill is very costly. More and better primary care facilities at the community level are needed. Cost-effectiveness in hospital management needs improvement, including rational use of diagnostic technologies and pharmaceutical products.

Diverse health insurance schemes are needed to improve consumer capacity to purchase needed services. Health care departments or bureaus need to strengthen their ability to monitor and regulate the performance of health care facilities. City governments will do well to actively plan for the development of their health services. The public also needs to be informed on available options in their choice of health care.

The rising number of elderly is creating a special challenge to health care. Most cities will not be able to provide them with the kind of hospital-based health care that those with full health insurance currently enjoy. Cities will be better off in meeting their needs through primary care and community support, and having them cared for in their own homes or in nursing homes. Any health insurance scheme would find it draining to fund health care for the elderly out of premiums paid by younger workers and contributions made by employers alone. Under that circumstance, governments should bear some of that cost; otherwise the whole health insurance scheme could fall flat.

For sure, it will be some time before everyone is fully insured. However, government can take other measures to protect the rest of the population. It can fund community health services and preventive programs adequately. It can encourage the development of cost-effective out-patient facilities. It can monitor and regulate the performance of the hospitals. It can reduce the over-prescription of drugs and over-utilization of health services. It can educate the public in many areas of health care. The government, under the Ministry of Civil Affairs, has begun to experiment with a safety net for health-maintenance in the poor, especially in the area of chronic illnesses, and to ensure that poor people have adequate access to essential health care.

One of the greatest challenges to city health departments is the changing nature of the populations they serve. Many localities outside city boundaries are becoming increasingly urbanized. These localities may be gradually integrated into the city. This will create many challenges to the provision of health services, the organization and financing of urban health services, and the ongoing reform in insurance schemes. As stated earlier, rural-to-urban migrants now constitute an important, but unknown, proportion of urban residents. Municipal governments need to take up the responsibility for their health care. There are two obvious reasons for it. First, these migrants are tax payers too and should be entitled to social benefits. Second, for public health reason, communicable diseases can be better controlled, as the importance of this issue was graphically illustrated during the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) outbreak. The employers of these migrant workers should be encouraged to enlist them in the Basic Health Insurance. This raises difficult questions about whether insurance benefits can be portable when these migrants return to their rural homes.

For the past 20 years the government has

responded rather passively to problems encountered by the urban health care

services as the country manages a rather swift and successful transition to a

market economy. Some of these problems include rapid rise in medical cost, and

many citizens are questioning how they can cope with the heavy financial burden

of a serious illness. Furthermore, adequate and equitable access to much needed

medical care remains a problem. The government has promised to give priority to

these problems. It remains to be seen how this will all pan out.

[1] People’s Republic of China, Bureau of Statistics, China Statistical Yearbook (Beijing: China Statistics Press, 2001).

[2] China Statistical Yearbook, 2001, Tables 10.3 and 10.9.

[3] China Statistical Yearbook, 2001,Table 3.9.

[4] China Statistical Yearbook, 2001,Table 10.5.

[5] China Statistical Yearbook, 2001,Table 5.4.

[6] China Statistical Yearbook, 2001,Table 5.1.

[7] Edward Gu, “Labor Market Insecurities in China” (Geneva: International Labor Office Publ., 2003), http://www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/ses/download/docs/labour_china.pdf (accessed May 14, 2008).

[8] Sarah Cook and Susie Jolly, “Unemployment, Poverty, and Gender in Urban China: Perceptions and Experiences of Laid-off Workers in Three Chinese Cities,” IDS Research Report, No. 50 (Brighton, England: University of Sussex, Institute of Development Studies, 2001); Chun-ling Li, “The Class Structure of China’s Urban Society during the Transitional Period,” Social Sciences in China, 23, no. 1 (2002): 91-99.

[9] China Statistical Yearbook, 2001.

[10] Alan Williams, “‘Need’ – an Economic Exegesis,” in The Economics of Health, ed. Anthony J. Culyer,vol. 1 (Brookfield, VT: Edward Elgar Pub., 1991), 259.

[11] Morris Barer et al., “Aging and Health Care Utilization: New Evidence on Old Fallacies,” Social Science and Medicine 24, no. 10 (1987): 851-62.

[12] Ai-hua Ou and Yan Zhu, “Analysis of Condition of Elderly People and Their Health Service Utilization in Guiyang City,” Chinese Primary Health Care 14, no. 3 (2000): 47-8; Li-ping Zhou and Rui-zi Wang, “Analysis of Health Need and Utilization of Elderly Population in Hangzhou City” [in Chinese], Journal of Zhejiang Medical University 27, no. 2 (1998): 84-87.

[13] Yue-gen Xiong, “Social Policy for the Elderly in the Context of Ageing in China: Issues and Challenges of Social Work Education,” International Journal of Welfare for the Aged, 1 (1999): 107-22.

[14] World Bank, China National Development and Sub-National Finance: A Review of Provincial Expenditures, Report No. 22951-CHA (Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 2002).

[15] Gerald Bloom and Sheng-lan Tang, eds., Health Care Transition in Urban China (Aldershot, Hants, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), 14.

[16] Joshua S. Horn, Away With All Pests: An English Surgeon in People’s China: 1954-1969, chap. 8(New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971), 70.

[17] De-quan Li, “The Right Direction in Providing Health Care for the People” [in Chinese], lecture delivered at the First National Health Conference, Beijing, Aug. 7-19, 1950, reported in People’s Daily Oct. 23, 1950, Editorial,http://read.woshao.com/400327 (accessed May 25, 2009).

[18] Bloom and Tang, 18.

[19] Bloom and Tang, 18.

[20] Dong-jin Wang, ed., The Reform and Development of China’s Social Security System [in Chinese] (Beijing: Falu Press, 2001), 278-79

[21] People’s Republic of China, “History and Development of Health Care System in Gansu Province” [in Chinese], Gansu, 2000.

[22] Wang, Reform and Development of China’s Social Security System,278-79.

[23] Chack-kie Wong et al., China’s Urban Health Care Reform (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2006), 14.

[24] Dong-jin Wang, “The Importance and Urgency of Sufficiently Understanding the Reform of the Health Insurance System for Urban Staff and Workers” [in Chinese], China Labor 158 (Jan. 1999): 4-7.

[25] Xiao-wu Song and Hao Liu, “The Reform of the Health Insurance System and Accompanying Measures,” in Report on the Reform and Development of China’s Social Security System [in Chinese], ed. Xiao-wu Song (Beijing: Renmin University of China Press, 2001), 83-106.

[26] Pei-yun Peng, Reform on Health Care System for Staff and Workers [in Chinese], report prepared for Social Security Department, People’s Republic of China (Beijing: Gaige, 1996), 3-21.

[27] Ibid., 4.

[28] Ibid., 3.